· deepdives · 7 min read

Exploring Security Implications of the Web Serial API: What Developers Need to Know

A deep, practical analysis of the Web Serial API's security risks and developer mitigations - from permission models and fingerprinting to firmware threats and secure design patterns you should adopt now.

What you’ll get from this article

You’ll leave with a clear threat model for the Web Serial API, a prioritized list of real-world attack scenarios, and pragmatic developer controls to reduce risk while keeping the benefits of direct device access in the browser.

Read on if you build web apps that talk to microcontrollers, industrial controllers, lab instruments, or any device exposed over a serial-like interface. This is about protecting your users, your devices, and your reputation.

Quick background: what the Web Serial API is (and how it behaves)

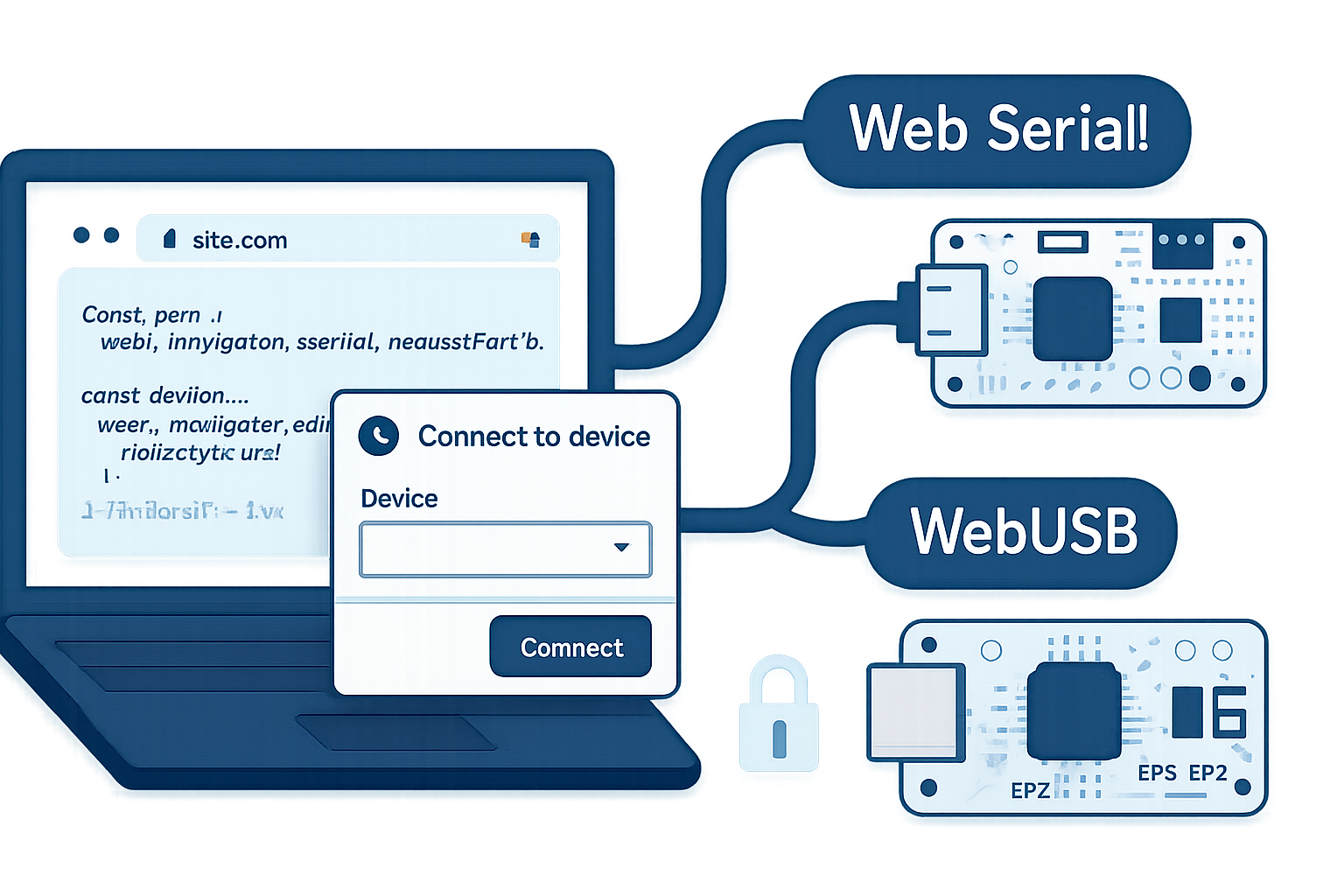

The Web Serial API exposes serial ports (e.g., USB CDC devices, UART-over-USB adapters) to web pages through JavaScript. It lets a site open a port, read and write bytes, and listen for connect/disconnect events. The spec and browser documentation explain capabilities and UX constraints in detail:

- WICG Web Serial spec: https://wicg.github.io/serial/

- MDN overview and API docs: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Serial

- Chrome developer guide: https://developer.chrome.com/articles/serial/

Important security-relevant characteristics you must keep in mind:

- Secure context only: the API requires HTTPS.

- User gesture required: port selection must be initiated by explicit user action (e.g., a click) via requestPort().

- Persistent permissions: browsers can remember granted access so subsequent visits may be able to call getPorts() without re-prompting.

- Origin scoping: access is granted to an origin, not to a particular subresource.

Those constraints help but do not eliminate risk.

Threat model: what we defend against (and what we don’t)

Defend against:

- Malicious or compromised web pages in the same origin that misuse a previously granted port.

- Cross-site scripting (XSS) that gains control of client-side script and uses the serial API.

- Rogue or malicious devices and firmware that abuse the port to attack the host or the web app.

- Browser extensions or OS-level malware that attempt to intercept or trick users into granting access.

Not covered here (but relevant in operations): hardware supply-chain compromises that replace devices at scale, or advanced side-channel attacks that require specialized lab equipment.

Real vulnerabilities and attack scenarios

Below are concrete ways things can go wrong. Each item includes why it matters and a realistic example.

- Unintentional persistent access abuse

Why: Browsers may persist permissions. Once a user grants access, scripts running later (or XSS) can continue to communicate with the device.

Example: A legitimate dashboard page has an XSS bug. An attacker injects a script that issues commands to a connected industrial controller via the serial port.

- Device as a pivot or network bridge

Why: Many devices have bridging capabilities (serial-to-ethernet, serial-modem, or AT-command-controlled cellular modems). If the web app can instruct a device to connect outbound, an attacker can exfiltrate data or create tunnels.

Example: Malicious code instructs a modem to dial out or open a socket, relaying internal data to an attacker.

- Sensitive data leakage and fingerprinting

Why: Serial devices often reveal serial numbers, firmware versions, or unique hardware IDs that can be used to fingerprint users or correlate visits across origins.

Example: A site reads a device serial number and reports it to analytics, enabling cross-site tracking.

- Malicious firmware and command injection

Why: Devices with weak firmware or command interpreters can be manipulated into unsafe states. Conversely, malicious devices can attempt to exploit host-side drivers.

Example: A counterfeit device sends specially crafted responses that trigger a host driver bug.

- Browser extension or OS-level compromise

Why: Local extensions or malware with access to the browser environment or OS can observe or trigger the device chooser or reuse persisted access.

Example: A compromised extension automates clicks and grants access to a port for a malicious origin.

- Insecure data handling and protocol confusion

Why: Serial data is raw bytes. Misinterpreting encodings, framing, or authentication messages can lead to replay or injection attacks.

Example: The app assumes newline-delimited JSON. An attacker injects control bytes that break parsing logic and escalate privileges on the connected device.

Developer mitigations - concrete controls you can implement today

The Web Serial API expands attack surface. But careful design and hygiene reduce risk dramatically. Here’s a prioritized, practical checklist.

- Respect least privilege

- Only request the exact port when the user intends to perform the action. Don’t call requestPort() on page load.

- Keep device sessions short. Close ports when idle.

- Require explicit, visible user consent and explain scope

- Use clear UI: show which device (with manufacturer/serial if available) you want to access and why.

- Remind users that granting access allows the origin to communicate with the device until permission is revoked.

- Harden your origin and client-side code

- Eliminate XSS: adopt strict Content Security Policy (CSP), use templating or safe frameworks, and sanitize all inputs. XSS is the easiest path for an attacker to misuse serial access.

- Use CSP, Subresource Integrity (SRI), and avoid inline scripts.

- Authenticate the device and the application protocol

- Do not trust device responses implicitly. Implement application-level mutual authentication where the device and the web app exchange nonces and verify signatures.

- Use challenge-response or cryptographic handshakes over the serial channel. If possible, require device firmware to support secure boot or signed firmware.

- Limit scope in code

- Map commands and only expose whitelisted operations to UI-driven flows.

- Use strict message parsers (reject too-long messages, unexpected bytes, or malformed frames).

- Logging, monitoring and alerting

- Log device connect/disconnect events and suspicious command sequences.

- Rate-limit operations and raise alerts on anomalous behavior (e.g., a sudden surge in outbound commands).

- Educate users and provide clear revocation paths

- Include UI to “Disconnect device” and instructions to revoke site permissions (browser-specific directions).

- Remind users not to connect untrusted devices.

- Use platform controls and headers

- Deploy over HTTPS and ensure secure cookies and HSTS.

- Use Permissions Policy to constrain which origins may use the serial feature (browser support varies). See Chrome guidance: https://developer.chrome.com/articles/serial/.

- Test against malicious firmware and corner cases

- Fuzz serial input handling and test boundary cases.

- Subject devices to negative testing: incorrect framing, long streams, out-of-band bytes.

- Operational recommendations for production

- Maintain a firmware verification program for supported devices.

- Consider device whitelisting on backends: associate device IDs with user accounts and verify on connection.

Design patterns: safe ways to integrate the API

- Isolate device logic in a small, well-audited module. Keep serial parsing separate from UI logic.

- Adopt a command/response protocol that includes versioning and authentication fields.

- Use a proxy architecture when appropriate: have the browser forward data to a backend that can enforce additional policies, rate limits, and auditing. (This sacrifices some low-latency benefits but adds control.)

Detection and incident response

If you suspect misuse:

- Instruct affected users to disconnect the device immediately and revoke site permissions in the browser settings.

- Collect logs: timestamps of connect/disconnect, commands sent, responses received.

- If devices are fielded in sensitive environments, proactively audit firmware and consider rotating credentials or re-flashing devices.

Policy and governance considerations

- Make a clear access policy for device-capable web apps: who can publish code that requests serial access, and what review gates must be met.

- Require threat model and acceptance tests for any page that uses the serial API.

- Keep an inventory of supported device models and their security properties.

Platform and vendor caveats

Behavior differs across browsers and OSes. Browsers are still evolving the UX and permission semantics. Relying solely on the browser’s permission model is insufficient - treat it as one layer among many.

For the latest platform specifics and recommendations, consult the browser vendor documentation and the spec:

- WICG Serial spec: https://wicg.github.io/serial/

- MDN Web Serial: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Serial

- Chrome developer guide: https://developer.chrome.com/articles/serial/

Short checklist - what you should do now

- Use HTTPS and require explicit user actions to request ports.

- Prevent XSS and lock down your CSP.

- Authenticate devices at the application level; avoid trusting raw serial inputs.

- Minimize permission lifetime and provide clear disconnect/revoke controls.

- Log, monitor, and test with malformed and malicious inputs.

- Educate users against connecting unknown hardware.

Closing: why this matters

The Web Serial API unlocks powerful, convenient capabilities for web apps. It also brings real risk - not abstract risk, but pathways for attackers to control hardware, exfiltrate data, and escalate from a browser exploit to physical-world consequences.

You can keep using the API safely. But you must design as if your JavaScript will be attacked. Harden your origin, validate and authenticate every byte that matters, and make permissioning transparent for users. Do that, and the Web Serial API becomes a useful tool rather than an unacceptable liability.