· deepdives · 6 min read

The Future of Web Applications: How the File Handling API is Revolutionizing Client-Side Storage

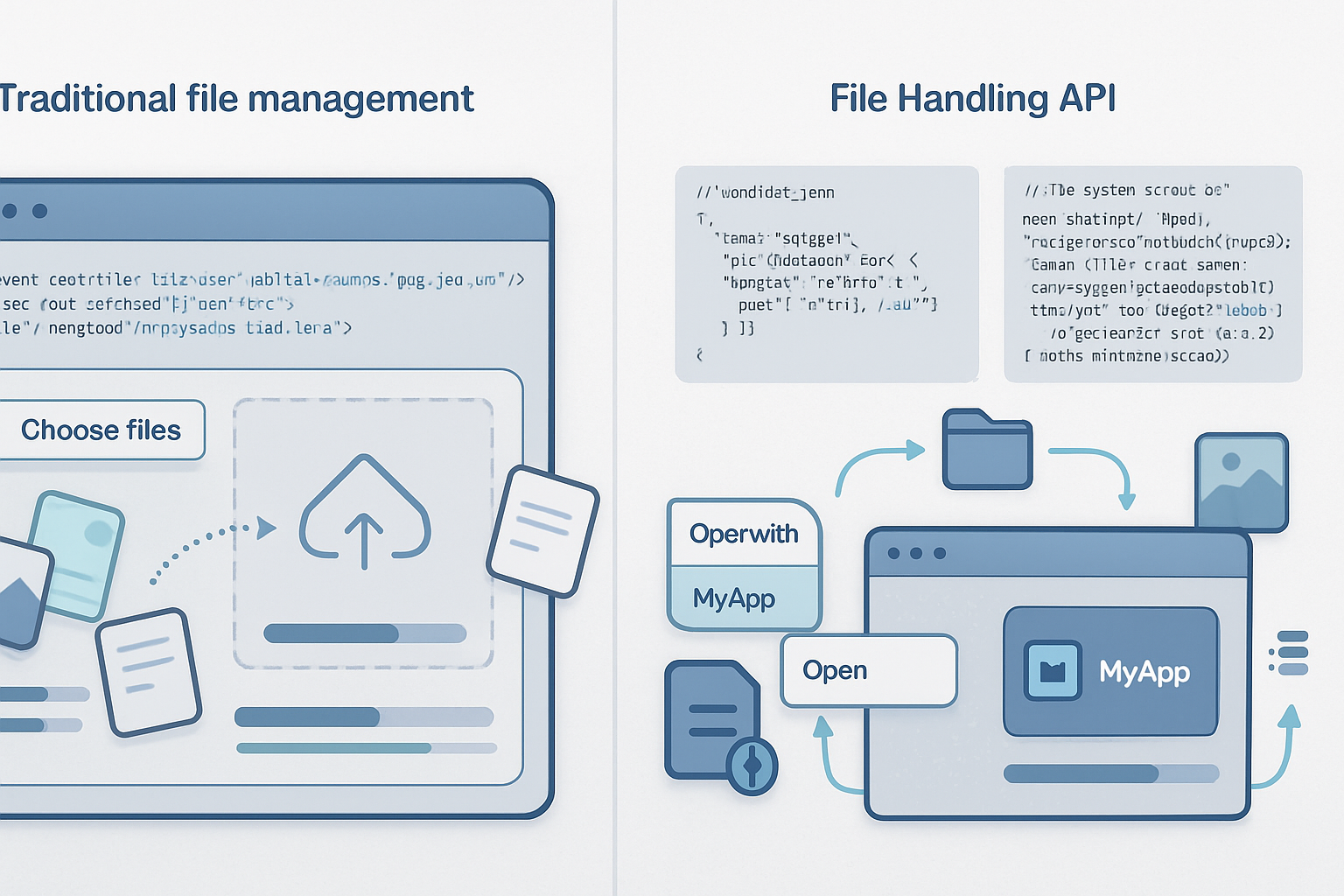

Discover how the File Handling API-and its ecosystem like the File System Access API and OPFS-lets web apps act like native file handlers, enabling powerful local-first storage patterns while reshaping privacy and security responsibilities for developers and users.

Outcome first: build web apps that open, edit, and persist real files on your users’ devices - without forcing uploads to a server. The File Handling API makes that possible. Read on and you’ll understand what the API does, how it changes client-side storage patterns, the security and privacy trade-offs, practical developer patterns, and where this technology is heading.

What the File Handling API actually does - in plain terms

The File Handling API lets a Progressive Web App (PWA) register itself as a handler for specific file types on the host OS. When a user opens a file of that type, the OS can launch the PWA and deliver the chosen file(s) to it. In short: your web app can behave like a native editor.

This is not about grabbing arbitrary files silently. It requires:

- That the app be installed (a PWA).

- A secure context (HTTPS).

- User-driven launch or explicit consent when opening files.

Official specs and explainers: see the WICG repo and Google’s developer guides for details: https://github.com/WICG/file-handling and https://web.dev/file-handling/.

Why this matters for client-side storage

Until recently, web apps typically handled user files by uploading them to a server. That pattern still makes sense for collaboration and server-side processing, but it creates friction and privacy exposure. The File Handling API changes that in three important ways:

- Native-like file workflows. Users can double-click a file on disk and open it directly in a web app, which preserves desktop mental models.

- Local-first application design. Combined with the File System Access API and OPFS (Origin Private File System), developers can read, write, and persist files locally without round-tripping to a server: fast, offline-capable, and often more private. See https://web.dev/file-system-access/ and https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/File_System_Access_API.

- Large-file handling becomes practical. Browser-based apps can stream and modify large files on disk without keeping the whole file in memory or uploading it.

Together these capabilities enable a new class of apps: local-first editors, heavy-media tools (video/audio/image editors), data-science clients, and single-device-first apps that only sync when users choose to.

How it works - a minimal example

Add file handler info to your web app manifest so the OS knows which MIME types or extensions your PWA can open:

{

"file_handlers": [

{

"action": "/",

"name": "Open with MyEditor",

"accept": {

"text/plain": [".txt"],

"application/vnd.myapp+json": [".myapp"]

}

}

]

}When launched with files, modern browsers expose the files through the Launch Queue API. Example handler in your page JavaScript:

if ('launchQueue' in window) {

launchQueue.setConsumer(async launchParams => {

const files = launchParams.files ?? [];

for (const handle of files) {

const file = await handle.getFile();

// Read or stream file content, show it in the editor

}

});

}Resources and guidance for these APIs are documented at https://web.dev/file-handling/ and the broader file-system docs at https://web.dev/file-system-access/.

Security and privacy implications - the core responsibilities

The File Handling API gives users convenience - and shifts responsibility to developers to protect their data. Key implications:

- User consent and discoverability: launches happen because the user invoked a file (or installed the PWA and accepted its role). There is no silent access to arbitrary files by simply visiting a site.

- Ephemeral vs persistent access: file data can be delivered at launch. Persistent editing access across sessions requires the File System Access API’s file handles, which are origin-scoped and require explicit user permission.

- Local-first ≠ automatically safer: storing files on-device avoids server-side exposure, but local data can be exfiltrated by malicious scripts, other installed apps, or by a compromised device. Developers must still practice secure handling.

- Regulatory context: local storage reduces cross-border transfer surface, but if an app later syncs data to a server it may still trigger obligations under laws like the GDPR - notably around data controllers, consent, and data access and deletion rights (see https://gdpr.eu/).

Best-practice checklist for developers

- Ask for the minimum. Only register file types your app actually handles, and only request persistent handles when necessary.

- Validate input. Never trust file extension alone; check MIME types and content where possible.

- Use origin-scoped storage and the OPFS for durable local data, and avoid writing secrets in plaintext. Use the Web Crypto API for on-device encryption as appropriate (https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Web_Crypto_API).

- Harden execution: follow Content Security Policy (CSP) best practices, sanitize any content that could be rendered as HTML, and run risky processing inside safe sandboxes or isolated workers.

- Be transparent with users: inform them how files are stored, when and how sync happens, and provide controls to export/delete local data.

References and recommendations from browser teams echo these practices: the Chrome team and the WICG working group provide guidance and explainer material at https://developer.chrome.com/articles/file-handling/ and https://github.com/WICG/file-handling.

Developer patterns unlocked by the File Handling API

- True offline editing workflows: open, edit, and save files without network connectivity. Upload or sync only when the user wants.

- Local-first collaborative workflows: store a canonical copy locally and use optional background sync or peer-to-peer protocols for sharing.

- Specialized tooling: photo/video editors, CAD viewers, IDEs, and analytics tools that need direct file-system integration and low-latency access.

- Hybrid cloud: process sensitive parts on-device, and only send derived metadata or non-sensitive results to the cloud.

These patterns pair well with IndexedDB, OPFS for structured storage, and the File System Access API for handle-based access. See https://web.dev/file-system-access/.

Threats and mitigation - practical advice

Threat: malicious or malformed files

- Mitigation: validate and sandbox parsing. Use robust, well-tested libraries for parsing complex formats.

Threat: persistent handles abused by compromised app code

- Mitigation: minimize persistent permissions; require re-consent for high-risk operations and rotate any device-bound keys.

Threat: sync accidentally leaks data to third parties

- Mitigation: default to opt-in sync with clear UI, and document what is synced.

Threat: cross-origin or persistent fingerprinting via file metadata

- Mitigation: avoid exposing more metadata than necessary. Adopt privacy-by-design: limit telemetry and make features opt-in.

Expert perspectives (from standards and browser teams)

Standards contributors and browser engineers have emphasized a common theme: the web should be able to offer native-like file workflows, but not at the cost of user control and security. The WICG file-handling proposal and Chromium’s engineering docs stress the need for install-time visibility, user gestures for granting access, and origin-scoped handles to limit abuse (https://github.com/WICG/file-handling, https://developer.chrome.com/articles/file-handling/).

Security-focused guidance from web platform teams consistently recommends treating local-first apps as distributed systems that still need secure defaults, strong input validation, and clear user consent flows. See the Web Platform docs on file-system access and Web Crypto for concrete APIs to help build secure flows: https://web.dev/file-system-access/ and https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Web_Crypto_API.

Where this is headed - three likely directions

- Broader cross-browser adoption. The APIs are maturing in Chromium; broader adoption will require feature parity and security reviews across engines.

- Richer offline-first ecosystems. Expect libraries and frameworks that make local-first sync, conflict resolution, and encrypted storage easier to adopt.

- More composable hybrid apps. The boundary between local and cloud will become a design choice per user action - not a technical requirement.

Bottom line

The File Handling API is a pivotal piece in the web’s evolution toward powerful, privacy-respecting, local-first applications. It lets developers build apps that feel native, handle large files well, and keep user data on-device - but it also makes secure design non-negotiable. If you’re building for the next generation of web apps, this API is not just an option. It’s a responsibility: build for convenience, and build with privacy and security at the core.

Further reading

- File Handling explainer and examples: https://web.dev/file-handling/

- File System Access API overview: https://web.dev/file-system-access/

- WICG File Handling proposal: https://github.com/WICG/file-handling

- Chrome developer article: https://developer.chrome.com/articles/file-handling/

- Web Crypto API (for on-device encryption): https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Web_Crypto_API

- GDPR overview (regulatory context): https://gdpr.eu/