· tips · 7 min read

Bizarre Bug Parade: Real-Life JavaScript Bugs That Shocked Developers

A tour of strange, real-world JavaScript bugs - why they happened, how they were fixed, and the concrete rules you can apply to avoid the same surprises in your codebase.

Introduction

What you’ll be able to do after reading this: recognize weird JavaScript failure modes quickly, apply pragmatic fixes, and design code that avoids the same traps. Read a handful of shocking, real-world bugs. Learn the root causes. Keep them from costing you hours or production incidents.

These stories are practical. They expose patterns, not just trivia. The strongest point: most of these disasters come from assumptions - about types, about the ecosystem, or about what the language silently does for you.

1) The Left-pad Collapse: dependency fragility that broke builds

The incident: in 2016 a tiny npm package called left-pad (11 lines) was unpublished and suddenly large swaths of the JavaScript ecosystem failed to build. Big companies and small packages crashed because they depended - directly or indirectly - on that one tiny module.

Why it shocked people: the break wasn’t a runtime bug in V8 or Node.js. It was an ecosystem-level fragility: transitive dependencies with deep trees and no lockfiles in some cases.

Reproduction (conceptual): uninstall left-pad from the registry and run npm install on a package that depends on it. Many builds fail.

Cause: trivial utility code was published and widely reused. The npm registry allowed unilateral removal at the time. Many packages assumed availability of tiny deps rather than bundling or copying necessary logic.

Fixes applied:

- npm and registry policy changes (scoped, ownership, and registry rules) and improved advice about lockfiles.

- Developers started pinning versions, vendoring, or reducing unnecessary tiny dependencies.

Lessons:

- Treat the dependency graph as part of your attack surface.

- Lock versions. Consider vendoring tiny utilities used in critical paths.

- Understand that package managers and registries are infrastructure you must account for.

Further reading: npm’s retrospective on the event Kik, left-pad, and npm.

2) parseInt and the leading-zero octal surprise

The bug: parseInt() without a radix historically treated strings with a leading 0 as octal in some implementations - so parseInt('08') could return 0 or NaN depending on engine and era.

Example:

// Dangerous: no radix provided

parseInt('08'); // historically inconsistent across engines

// Safe: always provide radix

parseInt('08', 10); // 8Cause: ECMAScript historical compatibility and varying engine behavior. Engines tried to be backwards compatible with C-style octal interpretation for 0 prefixes.

Fix: always pass the radix explicitly (e.g., parseInt(s, 10)) or use safer helpers like Number(s) or +s when parsing decimal integers.

Lesson: never rely on optional, implementation-dependent defaults.

Reference: MDN’s parseInt docs explain the radix gotcha parseInt - MDN.

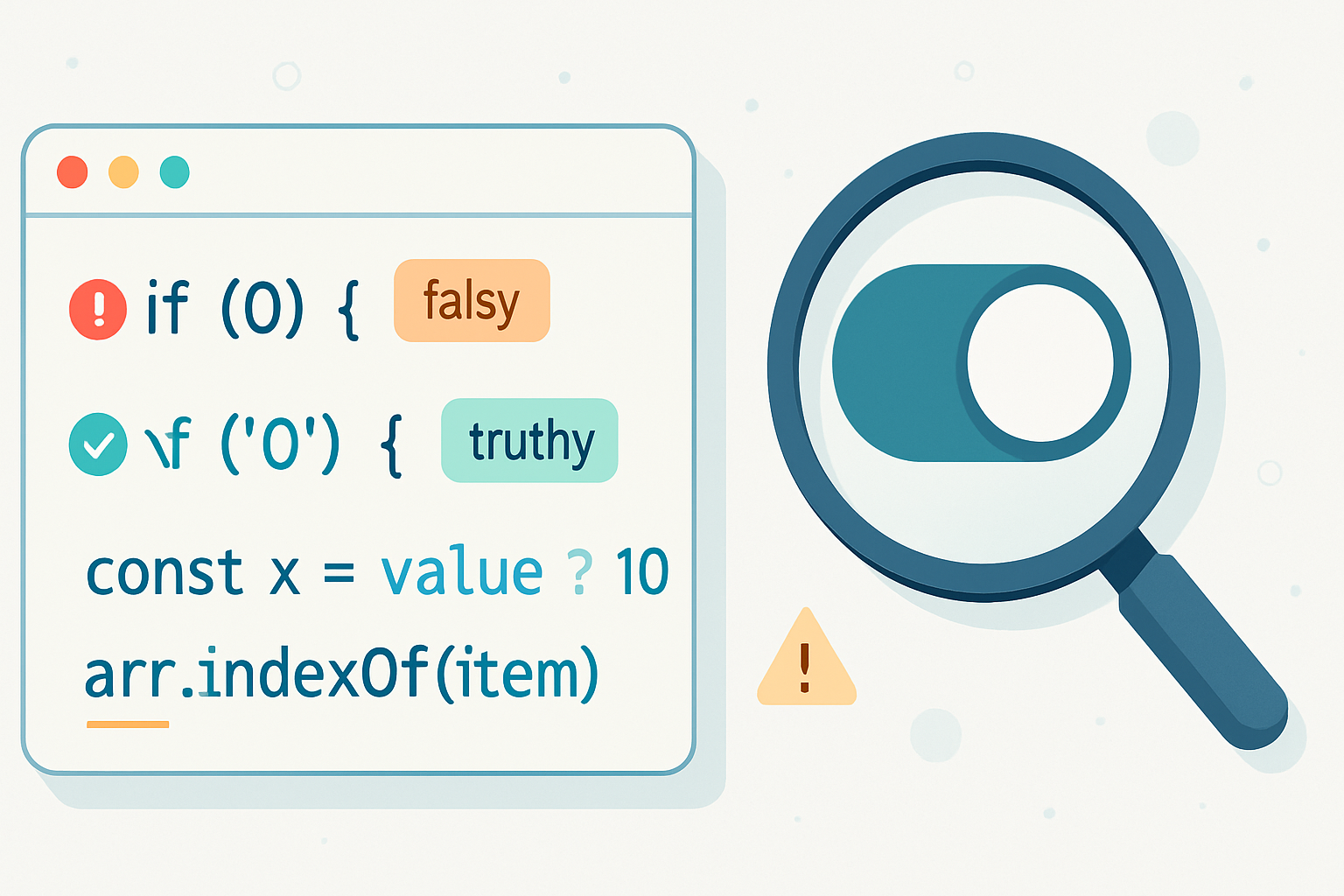

3) Automatic Semicolon Insertion (ASI) and the infamous return newline

The bug: JavaScript’s automatic semicolon insertion can silently insert a semicolon after a return if there is a newline immediately after, returning undefined instead of the intended object.

Example:

// Bug - returns undefined

function f() {

return;

{

ok: true;

}

}

// Correct - returns the object

function g() {

return {

ok: true,

};

}Cause: ASI is a convenience that tries to correct code with missing semicolons. Sometimes the correction is wrong for your intent.

Fix: Put the returned value on the same line as return, or use a linter/prettier rule to enforce semicolons or consistent styles.

Lesson: Be explicit with syntax in edge cases. Linters and formatting tools are your friends.

Reference: MDN on Automatic Semicolon Insertion Automatic semicolon insertion - MDN.

4) typeof null === ‘object’ - a language quirk that surprises newcomers

The bug: typeof null returns 'object'. That looks wrong: null is intentionally the absence of any object.

Why it happened: this is a long-standing bug dating back to the first JavaScript implementation. The representation used for values in early engines caused null to share a type tag with objects.

Example:

typeof null; // 'object'Fix / mitigation: Use explicit null checks (x === null) or helper functions (x == null to check null or undefined) and prefer robust type checks rather than just typeof.

Lesson: Understand language invariants and historical quirks. Assume that some built-in behaviors are legacy choices, not logical design.

Reference: MDN note on typeof typeof - MDN.

5) Floating point and toFixed rounding surprises

The bug: JavaScript numbers are IEEE‑754 doubles. That causes rounding surprises. For example, (0.615).toFixed(2) can yield '0.61' in some engines instead of the expected '0.62'.

Example:

(0.615).toFixed(2); // often '0.61' due to binary rounding

// For financial calculations, use integer cents or BigInt/decimal librariesCause: 0.615 cannot be represented exactly in binary floating point. Rounding steps introduce tiny differences that affect final textual rounding.

Fixes:

- For money, avoid floating-point. Use integers (cents) or a decimal library (e.g., decimal.js, BigInt with fixed scaling where appropriate).

- For display rounding, use well-tested helpers that implement the rounding mode you expect.

Lessons:

- Don’t treat JavaScript Number as a decimal; treat it as binary floating point and design accordingly.

- Pick the right numeric representation for business-critical math.

Further reading: discussions on rounding surprises like this are common on Stack Overflow and MDN’s Number docs Number - MDN.

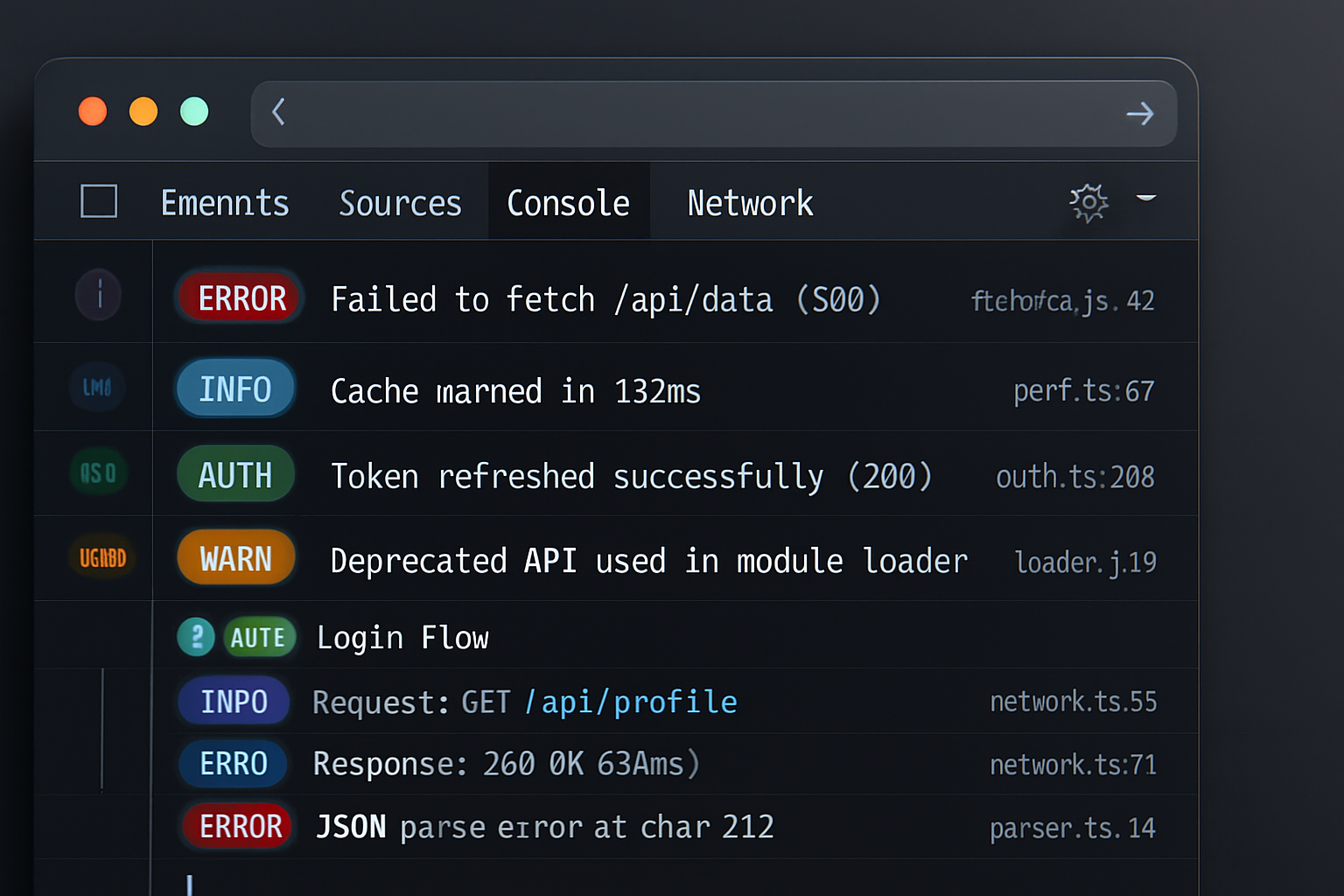

6) ReDoS: catastrophic backtracking in regular expressions

The bug: poorly written regular expressions can exhibit catastrophic backtracking - a specially-crafted input makes them consume exponential time, effectively creating a denial-of-service on your app.

Example (contrived):

const re = /(a+)+b/;

const evil = 'a'.repeat(30) + '!';

re.test(evil); // may take a long time in some enginesCause: nested quantifiers like (a+)+ force the regex engine to attempt many possible partitions while trying to match, leading to exponential backtracking.

Real-world impact: web forms, validation libraries, and user-supplied inputs have triggered ReDoS vulnerabilities; OWASP documents ReDoS as a common web vulnerability.

Fixes:

- Avoid catastrophic patterns. Prefer atomic groups, possessive quantifiers (when available), or rewrite the regex.

- Add input-length limits and timeout-based guards for expensive operations.

- Use vetted libraries for common validation tasks, and keep an eye on CVEs.

Lesson: user-controlled input + expensive pattern = trouble. Assume attackers will probe for worst-case inputs.

Reference: OWASP on ReDoS Regular expression Denial of Service - OWASP.

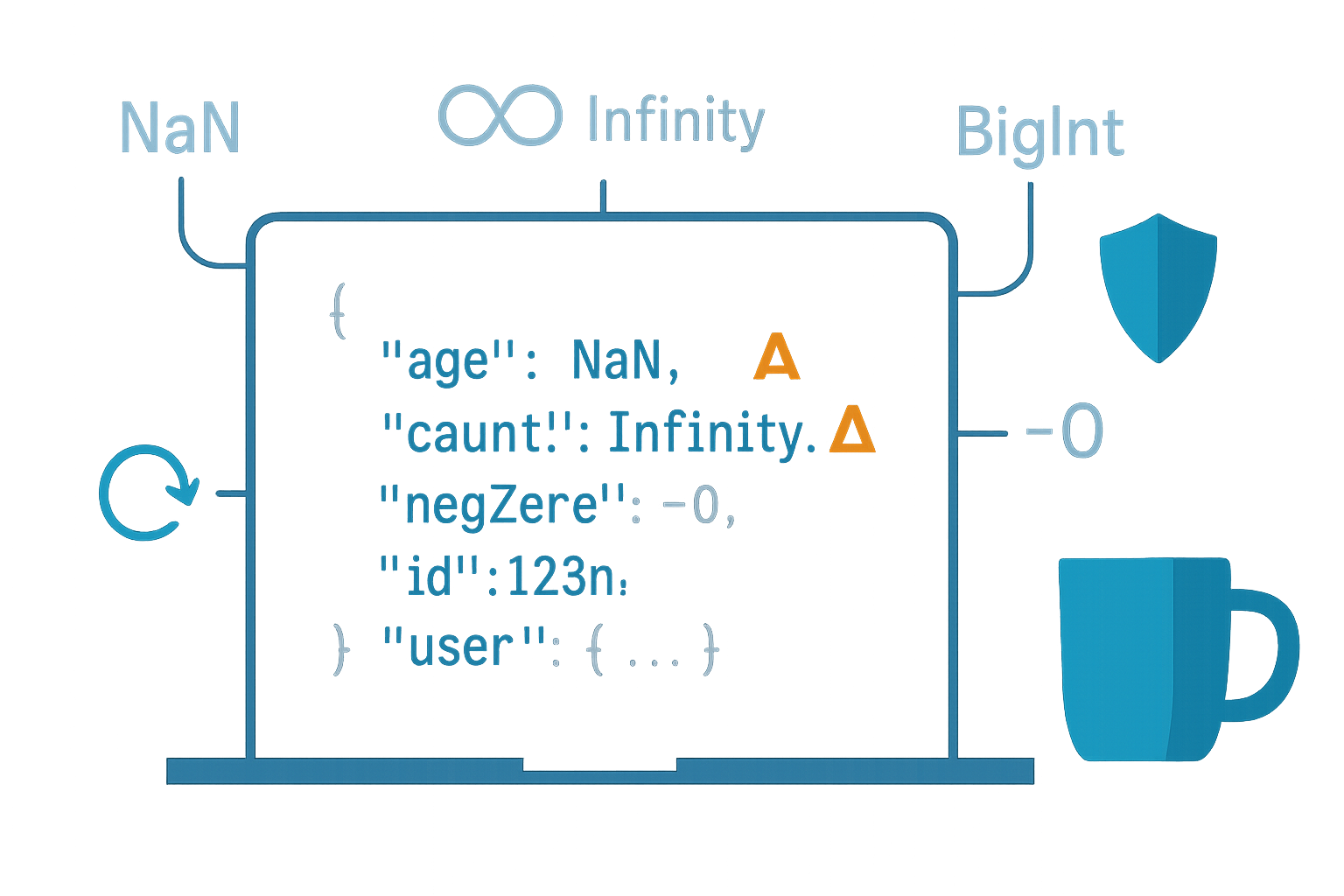

7) JSON integer precision loss - silent corruption of IDs and money

The bug: JSON numbers map to JavaScript Number (IEEE‑754 double). Integers larger than 2^53 - 1 lose integer precision. That silently corrupts big IDs, financial amounts, and timestamps.

Example:

const big = 9007199254740993; // Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER + 1

console.log(big); // 9007199254740992 - precision lost

// Round-tripping a JSON payload with big integers will lose precisionCause: JavaScript Number cannot precisely represent integers outside the 53-bit safe range.

Fixes:

- Send large integers as strings in JSON and parse them into BigInt or into a BigNumber/decimal type on the client.

- Use

BigInt(where supported) or libraries such asbig.js,decimal.js, orbignumber.js.

Lesson: choose wire formats and in-memory types according to the domain. IDs and money are not ordinary floating point numbers.

Reference: MDN on Number limits Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER - MDN.

8) Prototype extension and for…in enumeration surprises

The bug: libraries that extend Object.prototype (a practice some older libs used) suddenly make for...in loops iterate over library-added properties, breaking code that expected only own keys.

Real example: early conflicts between libraries that augmented global prototypes caused application code to behave unpredictably.

Example:

// If some library does:

Object.prototype.extra = function () {

/* ... */

};

// Then:

for (const k in user) {

console.log(k); // includes 'extra' unless hasOwnProperty is used

}

// Correct approach:

for (const k in user) {

if (!Object.prototype.hasOwnProperty.call(user, k)) continue;

console.log(k);

}Cause: JavaScript’s for...in enumerates enumerable properties on the prototype chain by design.

Fixes:

- Never augment built-in prototypes in libraries. It’s a famously bad pattern.

- When iterating, use

Object.keys()/Object.values()/Object.entries()orhasOwnPropertychecks.

Lesson: APIs that mutate global prototypes are social liabilities. Prefer composition over pollution.

Reference: MDN on for…in and prototype pitfalls for…in - MDN.

Practical checklist to avoid these and similar disasters

- Audit dependencies and lock versions. Vendor critical tiny functions.

- Add static analysis and linters. Enforce style and safe patterns (radix for parseInt; avoid ambiguous returns; disallow prototype pollution).

- Limit input sizes, and guard expensive operations (regexes, big loops) with timeouts or length checks.

- Use the right numeric type for the job: integers for money/IDs, BigInt or decimal libraries when needed.

- Test edge cases: long strings, boundary numbers, null/undefined/NaN, international inputs.

- Keep a changelog for third-party updates and automate selective rollouts (canary). Assume the ecosystem can break in unexpected ways.

Closing thought

Most of these bizarre bugs share one root cause: fragile assumptions. Assumptions about defaults, about the ecosystem, and about the cost of operations. The antidote is simple: make fewer assumptions, encode expectations as tests and rules, and treat the JavaScript runtime and its ecosystem as an explicit part of your system design. Do that, and you’ll catch the parade of strange bugs before they parade into production.