· deepdives · 7 min read

Debunking Myths: Is the Screen Wake Lock API a Privacy Risk?

The Screen Wake Lock API prevents devices from dimming or sleeping. This article separates real privacy risks from myths, explains how the API works, shares expert perspectives, outlines threat models, and gives safe alternatives and best practices for web developers and users.

Outcome-first: by the end of this piece you’ll be able to judge whether the Screen Wake Lock API truly threatens user privacy, explain how browsers mitigate risks, and implement safer wake-lock behavior in your web app.

Short answer (the hook)

No - the Screen Wake Lock API itself does not leak user data or allow tracking in the way camera, microphone, or geolocation do. But like any capability that affects device behavior, it can be misused for nuisance, battery drainage, or to help other signals infer presence. Understand the threat model, follow a few defensive patterns, and you’ll have minimal risk.

What the Screen Wake Lock API actually does

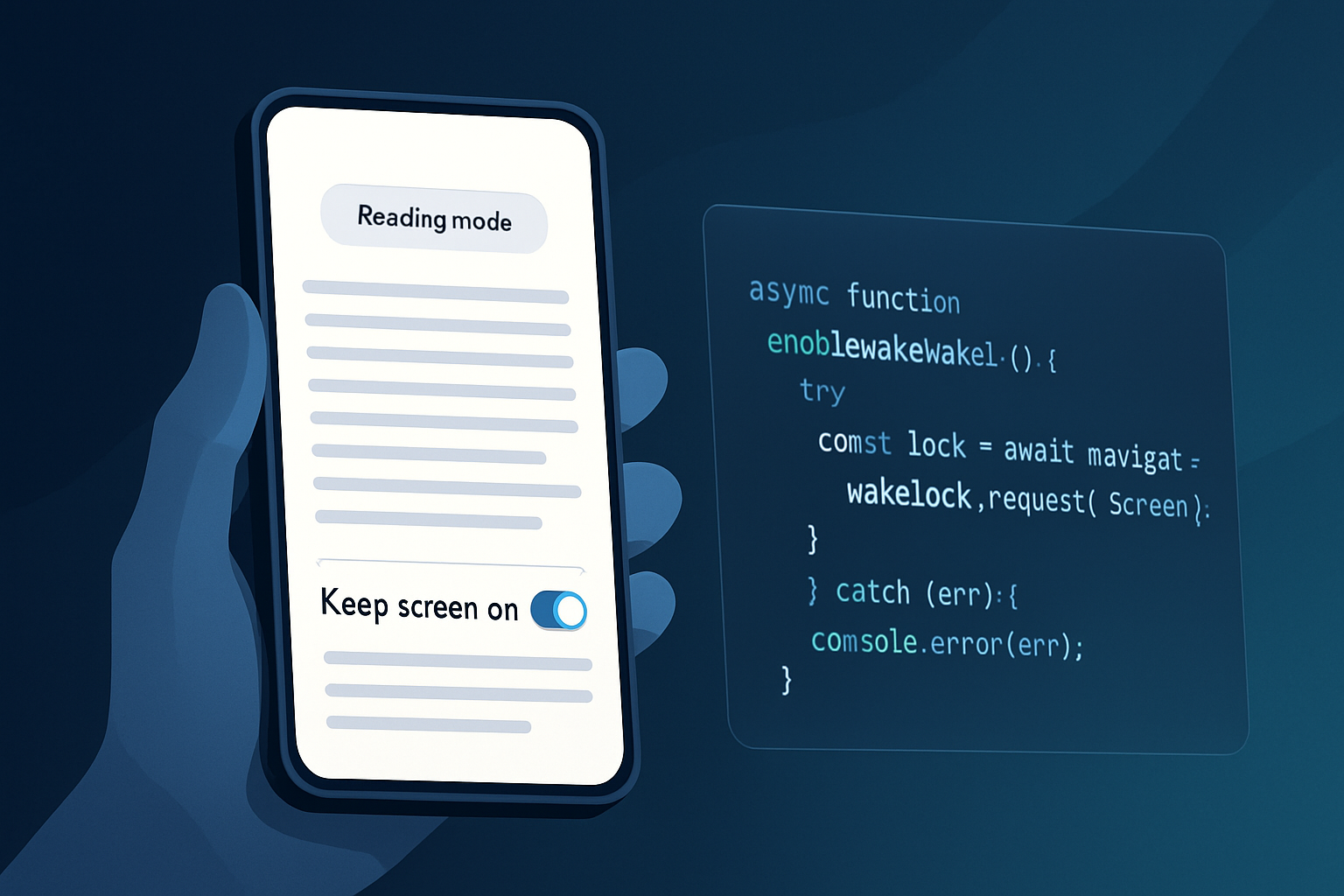

The API provides a programmatic way for a web page to request that the device keep the screen on (prevent dimming or sleeping) while the page is active. The common call looks like this:

// request a screen wake lock

let wakeLock = null;

async function requestWakeLock() {

try {

wakeLock = await navigator.wakeLock.request('screen');

wakeLock.addEventListener('release', () => {

console.log('Wake lock released');

});

console.log('Wake lock acquired');

} catch (err) {

console.error('Failed to acquire wake lock:', err);

}

}

// remember to release when you no longer need it

async function releaseWakeLock() {

if (wakeLock) await wakeLock.release();

}The API is gated to secure contexts (HTTPS) and subject to user-agent policies. For implementation details and spec rationale see the W3C Working Group’s Wake Lock specification and MDN documentation: https://w3c.github.io/wake-lock/ and https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Screen_Wake_Lock_API

Why people worry: the claimed privacy risks

Common concerns people raise include:

- “A site could keep my device awake indefinitely and drain my battery.” (Usability / resource abuse)

- “Sites could use wake-lock behavior as an additional signal for fingerprinting or inferring presence/activity.” (indirect tracking)

- “Because there’s no permission prompt, it means no user consent - a privacy hole.” (consent model)

- “Combined with other APIs, wake lock could be part of a more invasive surveillance setup.” (composability risk)

Each concern has merit in context. But context matters.

Reality check - how risky is it, really?

Data leakage: The wake-lock API does not expose camera, microphone, sensors, or identifiers. It simply requests that the screen stay on. There is no direct channel in the API for reading user data.

Tracking & fingerprinting: Wake-lock usage could be incorporated as a boolean feature in a fingerprint, but that is weak on its own. Fingerprinting usually relies on many high-entropy signals. Wake lock adds little unique entropy and is ephemeral and easily observable by user-agent heuristics.

Battery / nuisance abuse: This is the clearest real risk. A malicious or careless site can keep the screen on, depleting battery and creating a bad UX. This is not strictly a “privacy leak” but it affects user autonomy and can indirectly facilitate other threats (e.g., keeping a device useable while an attacker executes client-side tasks).

Consent & visibility: Most browsers do not create a permission prompt for wake lock. Instead, they restrict use (for example, require user gesture to initiate, restrict when the document is hidden, and let the UA revoke locks under power-saving policies). That design treats wake lock as a capability-with-constraints rather than a privacy-sensitive sensor.

For a platform-level explanation and design rationale see the W3C wake lock spec and the MDN guide: https://w3c.github.io/wake-lock/ and https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Screen_Wake_Lock_API

Browser behavior and mitigations you should know

- Secure contexts only: wake locks work only on HTTPS pages (or localhost), reducing man-in-the-middle risks.

- UA heuristics: many browsers will silently revoke or refuse a wake lock in low-power modes or when the tab is backgrounded. This prevents indefinite battery abuse.

- Visibility integration: developers are encouraged to release wake locks on visibility change; many example implementations do that automatically.

- No persistent permission prompt: instead of showing a permission dialog, browsers enforce runtime constraints and revocation policies.

These implementation choices intentionally reduce the worst practical abuses while keeping the API useful for legitimate apps (video players, fitness timers, presentation tools, kiosk apps).

Expert perspective (consensus view)

Standards authors designed wake lock as a limited capability - not a sensor - and therefore treated it differently from high-risk APIs like camera or microphone. See the W3C spec rationale: https://w3c.github.io/wake-lock/

Documentation like MDN highlights that wake locks should be used sparingly and released promptly; they also document that user agents can limit behavior: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Screen_Wake_Lock_API

Taken together the consensus is: the API is low-risk for direct privacy leaks, but it must be used responsibly and browser policies should continue to guard against resource abuse.

Realistic threat models

Think in concrete terms. Here are scenarios ranked from most to least plausible:

Battery/UX abuse (plausible): A site intentionally keeps a visitor’s screen active to maximize ad impressions or keep a background script functioning. Result: drained battery and annoyed user.

Indirect tracking (possible but weak): A site uses the presence or absence of a wake-lock call, combined with other subtle signals, to augment a fingerprint. This alone won’t identify users reliably but may be part of a broader tracking apparatus.

Surveillance pairing (theoretical): Wake lock keeps the screen on while another mechanism collects data (e.g., on a kiosk). The wake lock itself didn’t collect data - it just prolonged an opportunity for data collection.

Direct data exfiltration (very unlikely): The API doesn’t provide data channels - it can’t read sensors or identifiers by itself.

Practical recommendations for developers (how to use wake lock safely)

- Request only when necessary. Ask if the feature truly needs the screen kept on.

- Request on user gesture (start button) to align with user intent.

- Release promptly: on task completion, on visibilitychange, or before unloading.

- Provide UI feedback: show an icon or message indicating “Screen will stay on” so users know the device state.

- Respect power-saving modes: listen for events and gracefully degrade.

- Document the behavior in your privacy policy - be transparent.

Example pattern (visibility-aware):

let wakeLock = null;

async function enableWakeLock() {

try {

wakeLock = await navigator.wakeLock.request('screen');

wakeLock.addEventListener('release', () => {

console.log('Wake lock released by UA or system');

});

} catch (err) {

console.error('Could not obtain wake lock', err);

}

}

// Re-obtain after visibility changes (common pattern)

document.addEventListener('visibilitychange', async () => {

if (document.visibilityState === 'visible' && wakeLock === null) {

await enableWakeLock();

} else if (document.visibilityState === 'hidden') {

if (wakeLock) await wakeLock.release();

wakeLock = null;

}

});Safe alternatives and fallbacks

- Native apps: If your use case is mission-critical (medical device, kiosk), use a native app API that offers clearer OS-level user consent and management.

- Progressive Web App (PWA) + Wake Lock API: If supported, continue using the API but follow best practices above.

- NoSleep.js / video-play hacks: Historically developers used a small looping video or libraries like NoSleep.js (https://github.com/richtr/NoSleep.js) as a workaround on platforms that lacked wake lock support. This is a hacky fallback, may consume more power, and is noisier from a privacy/UX standpoint - avoid if you can.

Recommendations for users and policymakers

- Users: be wary of sites that keep your device awake without clear purpose. Close the tab or revoke access (if your browser provides controls). Monitor battery drain caused by particular sites.

- Policymakers & browser vendors: continue to treat wake lock as a capability that requires careful UA-level heuristics and transparency. Consider adding clearer user controls (an indicator or settings toggle) so users can easily see which pages are keeping the screen awake.

Final verdict: myth-busted with caveats

The Screen Wake Lock API is not a direct privacy risk in the sense of exposing personal data or enabling fingerprinting by itself. The real, practical concerns are battery abuse, nuisance behavior, and the potential for wake lock to extend opportunities for other forms of data collection. The platform’s current approach - secure contexts, UA heuristics, and developer guidance - strikes a pragmatic balance.

If you’re a developer: request wake lock carefully, show clear UI, and release it promptly. If you’re a user: watch for sites that keep your screen on without a clear reason and close them. With those practices in place, the wake-lock API is a useful tool that doesn’t warrant the alarmist privacy headlines it sometimes receives.

References

- W3C Wake Lock API specification: https://w3c.github.io/wake-lock/

- MDN: Screen Wake Lock API: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Screen_Wake_Lock_API

- NoSleep.js (historical fallback): https://github.com/richtr/NoSleep.js