· tips · 7 min read

The Mystery of Microtasks vs. Macrotasks: A Deep Dive

Understand how microtasks and macrotasks differ in the JavaScript event loop, see compact examples that expose surprising ordering and starvation issues, and learn practical patterns to use each correctly in browsers and Node.js.

Outcome first: after reading this you’ll be able to predict why Promise.then runs before setTimeout, why a long chain of microtasks can freeze rendering, and how to pick the right scheduling primitive to avoid subtle bugs and performance traps.

Why this matters (quick)

You write asynchronous code all the time: Promises, setTimeout, requestAnimationFrame, Node timers. But those primitives don’t just run “sometime later” - they participate in the event loop with different priorities. That ordering causes surprising results: UI not updating, I/O delays, or code appearing to re-enter unexpectedly. Learn the rules and you stop being surprised.

The big picture: tasks, microtasks, rendering

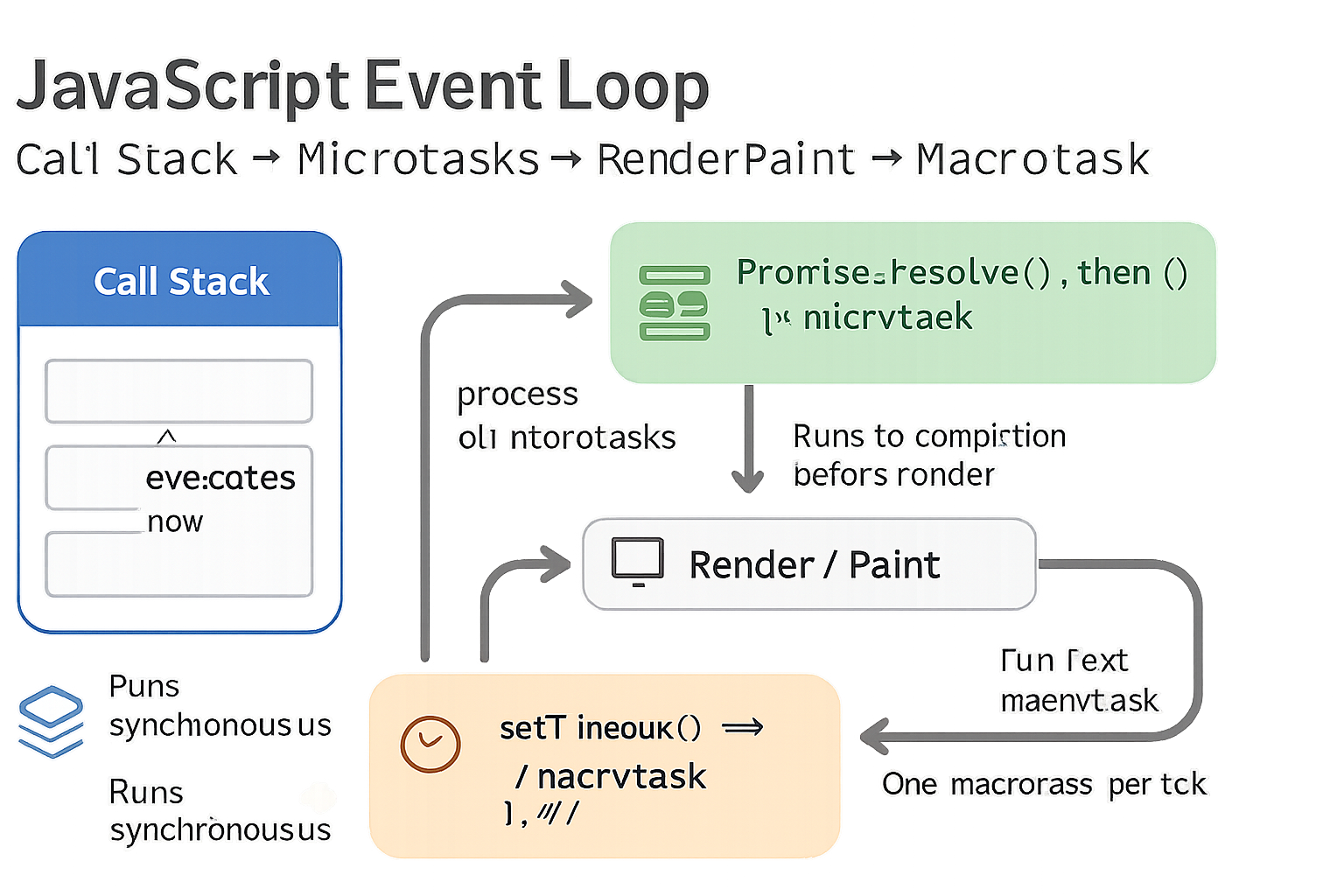

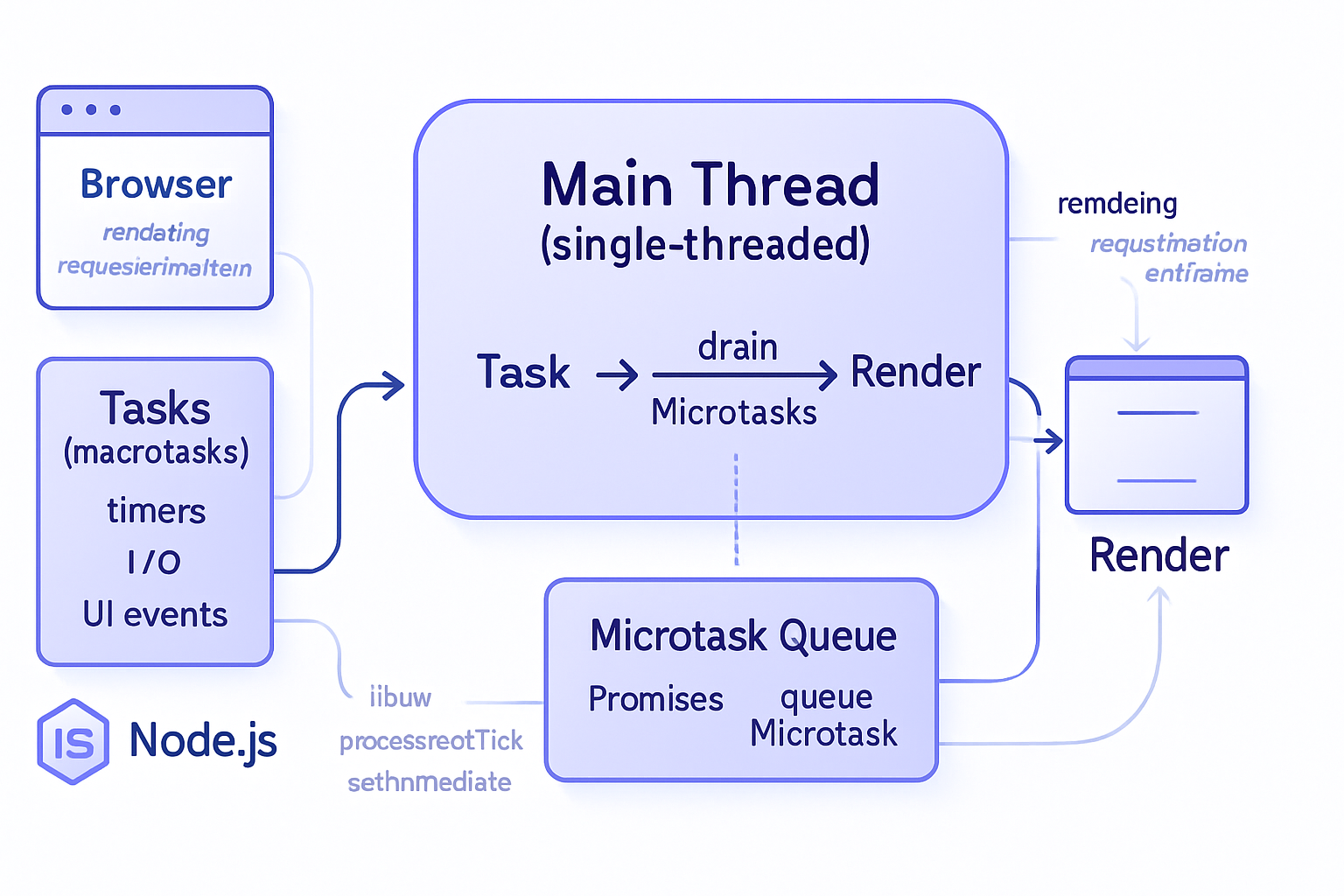

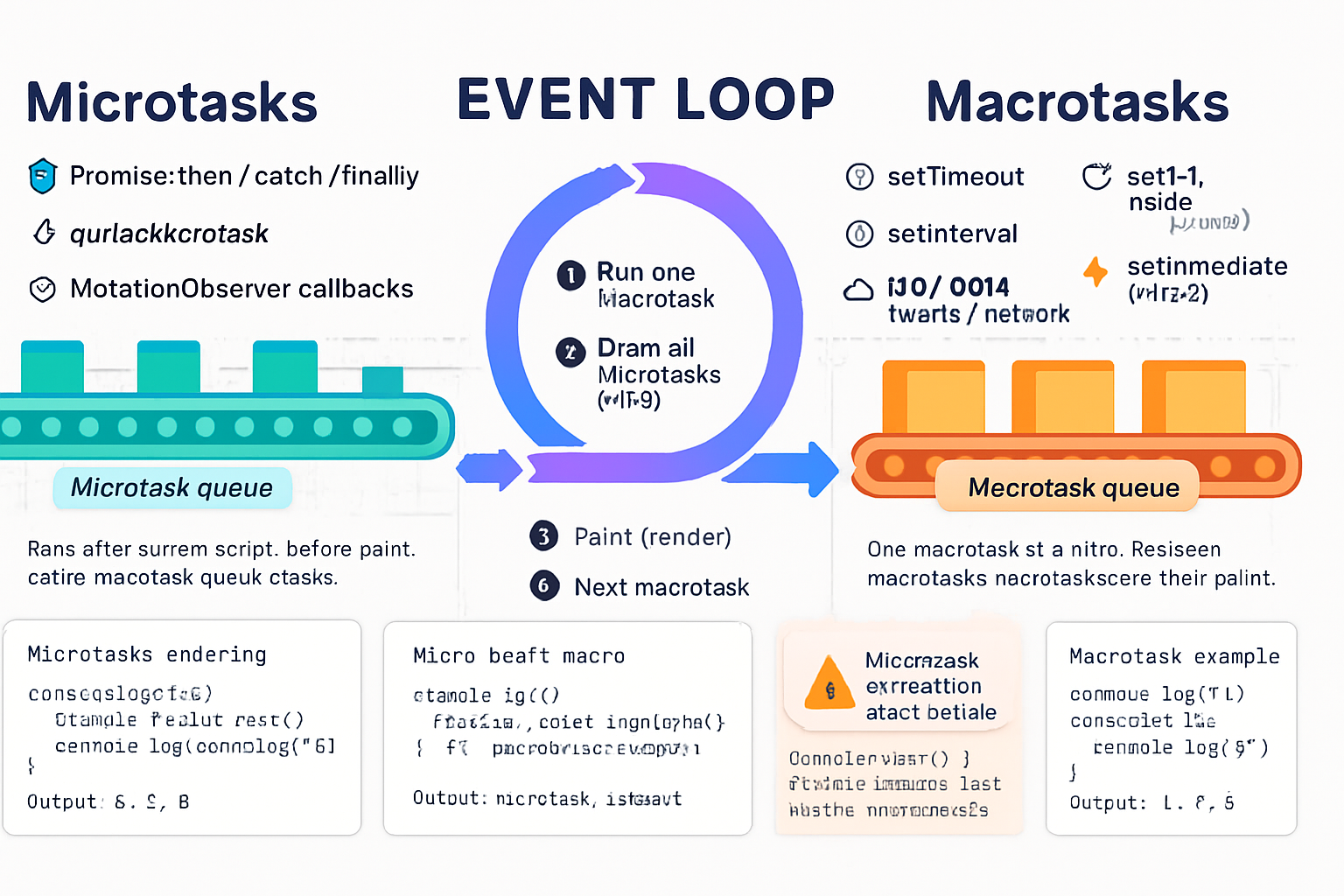

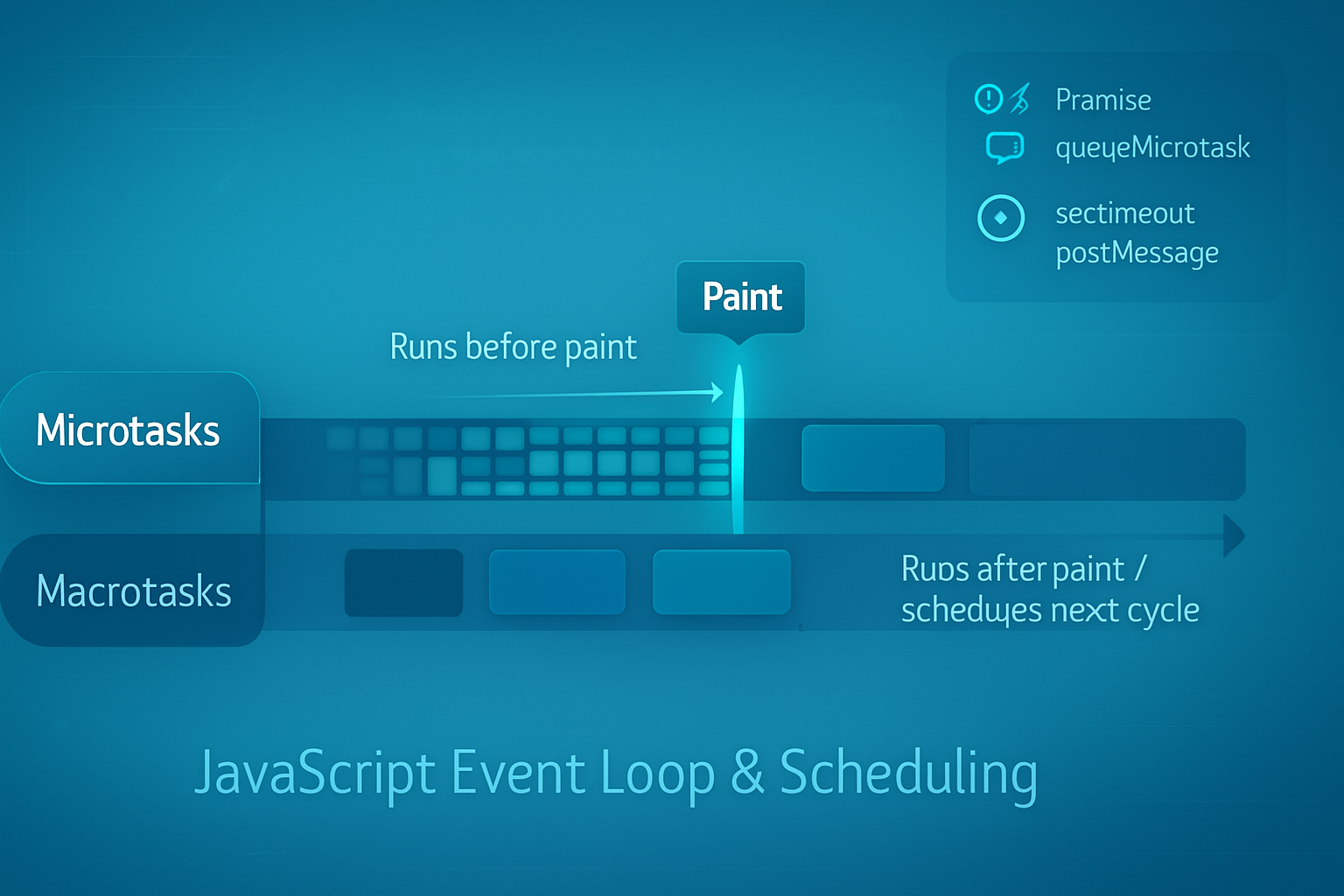

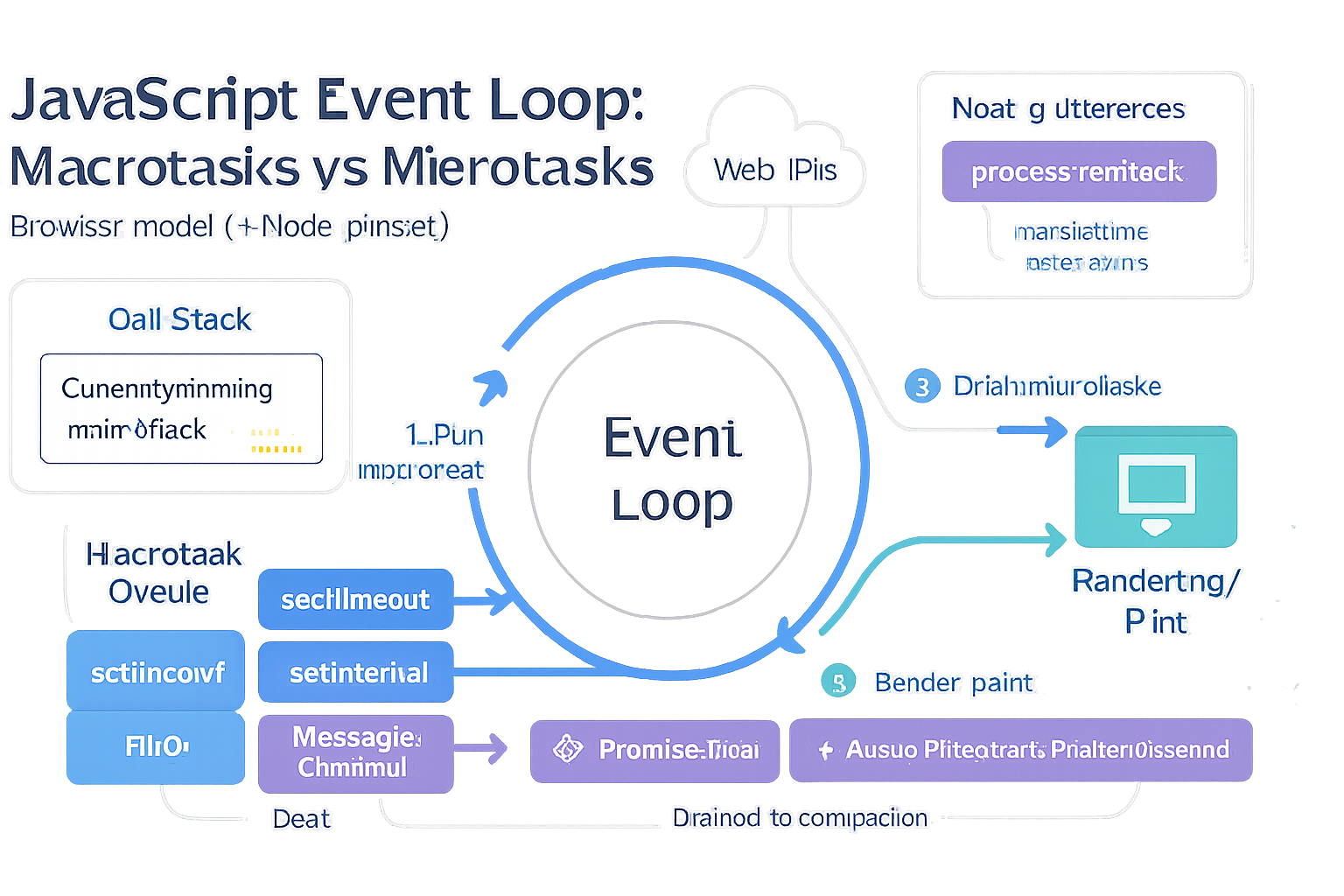

At a high level the event loop repeatedly does work in cycles. Each cycle executes one macrotask (often just called “task”), then runs all queued microtasks, then (in browsers) may perform rendering, and finally starts the next macrotask. The important bits:

- Macrotasks: things like setTimeout callbacks, setInterval, I/O callbacks (in Node), message events, and user interaction callbacks. These are scheduled into the task queue.

- Microtasks: Promise callbacks (.then/.catch/.finally), queueMicrotask, MutationObserver callbacks. They form a separate queue that is processed immediately after the currently running macrotask finishes - before rendering and before the next macrotask.

Browser-friendly summary: run one macrotask → run all microtasks (until empty) → paint/update UI → next macrotask. See MDN for an authoritative explanation: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/EventLoop

Jake Archibald’s classic deep dive is also must-read: https://jakearchibald.com/2015/tasks-microtasks-queues-and-schedules/

Node differs slightly: it has phases (timers, pending callbacks, idle/prepare, poll, check), plus distinct queues like process.nextTick and the microtask queue (Promises). process.nextTick runs before the microtask queue and can starve I/O if abused. Node event loop docs: https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick/

Concrete ordering examples (learn by looking)

Browser example: microtasks before macrotasks

console.log('script start');

setTimeout(() => console.log('setTimeout (macrotask)'), 0);

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise.then (microtask)'));

console.log('script end');

// Typical output:

// script start

// script end

// promise.then (microtask)

// setTimeout (macrotask)Notice: even though both callbacks are scheduled “after” the current script, the Promise callback runs before setTimeout because microtasks run between macrotasks.

Node example: process.nextTick outruns Promises

console.log('start');

process.nextTick(() => console.log('nextTick'));

Promise.resolve().then(() => console.log('promise'));

setTimeout(() => console.log('timeout'), 0);

console.log('end');

// Typical output in Node:

// start

// end

// nextTick

// promise

// timeoutprocess.nextTick has higher priority than the Promise microtask queue. That power can be abused (see starvation below).

Surprising use cases and the unexpected results they produce

Below are practical, surprising scenarios that are good to know - and a short explanation of why they happen.

1) Microtask chains can starve rendering (UI freezes)

If you keep scheduling microtasks from microtasks (for instance, repeatedly calling queueMicrotask or chaining huge numbers of Promise.then handlers), the browser will keep executing microtasks and will not yield to rendering until the microtask queue is empty. The result: no painting, frozen UI.

Example pattern that can freeze the page:

function busyMicrotasks(n) {

if (n <= 0) return;

Promise.resolve().then(() => busyMicrotasks(n - 1));

}

busyMicrotasks(1e6);Because microtasks run to completion between macrotasks, the page won’t paint while that chain runs.

When you want to keep the UI responsive, break work into macrotasks so the browser can render between chunks: use setTimeout(…, 0), setImmediate (Node), or better: requestAnimationFrame when you need to align with paint frames.

2) Batching synchronous-looking updates with microtasks (a feature)

Frameworks use microtasks intentionally for batching. If multiple state updates happen synchronously, deferring reactions into a microtask lets the framework coalesce updates and perform one DOM patch.

Example: in many frameworks you’ll see a “nextTick” helper implemented with Promise.resolve().then(…). That ensures code runs right after the current call stack but before the browser paints - perfect for checking DOM state after all synchronous changes have been applied.

This is how Vue’s nextTick behaves in modern builds (microtask-based) and how React’s flush behaviors are scheduled in certain modes.

3) process.nextTick starvation in Node

In Node, process.nextTick runs before other microtasks and before I/O callbacks. If you schedule infinite nextTick work, the event loop will never reach the I/O phase and your network/FS callbacks will be starved.

Bad example:

function spin() {

process.nextTick(spin); // never yields to I/O

}

spin();Use nextTick sparingly. For deferring without starving, prefer setImmediate or a microtask (Promise) depending on your goal.

4) When setTimeout 0 is not ‘immediate’ - you can get bigger-than-expected delays

setTimeout(…, 0) is a macrotask scheduled into the timers phase. Browsers often enforce minimum timer clamping (e.g., 4ms for nested timers) and guarantee clamping in background tabs. If you need near-immediate scheduling, microtasks or MessageChannel are faster. But remember microtasks run before painting, and can cause the starvation discussed above.

MessageChannel provides a lower-latency macrotask-like callback than setTimeout in some environments and is often used to implement zero-delay task queues in libraries.

5) Reentrancy surprises: a microtask can run while your code expects no callbacks

Because microtasks run right after the current macrotask, code that assumes “no callbacks will run until next tick” can be surprised by Promise.then running mid-operation if you or a library uses it. That can cause subtle race conditions when code mutates shared state and doesn’t expect microtask callbacks to observe half-finished state.

Defensive pattern: if you need to guarantee a callback runs only after the current logical operation (including microtask reactions) finishes, use a macrotask (e.g., setTimeout or requestAnimationFrame) to schedule it later.

6) MessageChannel for cooperative scheduling and priority control

You can use MessageChannel to create a low-overhead macrotask queue that often runs quicker than setTimeout(0). It also avoids timer clamping. Libraries use this for task queues when they want quick but yielding execution.

const mc = new MessageChannel();

const q = [];

mc.port1.onmessage = () => q.shift()();

function postTask(fn) {

q.push(fn);

mc.port2.postMessage(0);

}

postTask(() => console.log('run soon as a macrotask'));This schedules a task that will run after the current macrotask finishes and after microtasks have drained - but before setTimeout in many cases.

Rules of thumb (practical guidance)

- Use microtasks (Promise.then, queueMicrotask) when you want work to run immediately after current synchronous code completes, and before rendering. Great for batching and consistent sequencing.

- Use macrotasks (setTimeout, setImmediate, MessageChannel) when you need to yield to rendering, allow I/O to proceed, or avoid reentrant reads of application state.

- Use requestAnimationFrame for visual work that must occur right before the next paint.

- In Node, avoid unlimited process.nextTick chains - they can starve I/O. Use setImmediate or Promise microtasks depending on desired timing.

- When performance or fairness matters, chunk long work into macrotasks so the system can respond to input and paint frequently.

Quick checklist to diagnose surprising behavior

- If Promise.then runs before your timer: that’s expected - microtasks win.

- If the UI doesn’t update until long after you change the DOM: check for heavy microtask work or a tight loop preventing paint.

- If Node I/O callbacks are delayed: look for heavy process.nextTick usage.

- If setTimeout(0) seems slow: consider timer clamping or use MessageChannel/requestAnimationFrame depending on the context.

Short patterns you can copy

Batching synchronous updates into one microtask:

let scheduled = false;

function scheduleBatch(cb) {

if (!scheduled) {

scheduled = true;

Promise.resolve().then(() => {

scheduled = false;

cb();

});

}

}

// multiple calls to scheduleBatch in the same tick -> one cbYield to the browser to keep the UI responsive:

function chunkedWork(items) {

function doChunk() {

const start = Date.now();

while (items.length && Date.now() - start < 10) {

processItem(items.shift());

}

if (items.length) setTimeout(doChunk, 0); // yield and allow paint

}

doChunk();

}Prefer requestAnimationFrame for animation-aligned work:

function animateStep() {

// mutate DOM for next frame

requestAnimationFrame(animateStep);

}

requestAnimationFrame(animateStep);Final thoughts (what to remember)

The event loop is a simple machine with two useful levers: microtasks for immediate, in-between-work reactions, and macrotasks for chunking and yielding. Use microtasks to batch and order. Use macrotasks to yield and be fair to rendering and I/O. Remember Node’s special queues (process.nextTick, setImmediate) and the way they can change priorities.

Master these distinctions and you’ll stop being surprised by ordering issues, mysterious UI freezes, and odd I/O delays. The event loop is predictable - once you think in terms of “run macrotask → drain microtasks → paint → macrotask” you’ll pick the right tool every time.

References

- MDN: Event loop - https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/JavaScript/EventLoop

- Jake Archibald: Tasks, microtasks, queues and schedules - https://jakearchibald.com/2015/tasks-microtasks-queues-and-schedules/

- Node.js Guide: Event loop, timers, and process.nextTick - https://nodejs.org/en/docs/guides/event-loop-timers-and-nexttick/